On August 3, 2011, we dismissed our law firm, Lane Powell, and hired another firm to take us through the remand on our case. We had already paid Lane Powell $313,253.00. On the day we dismissed the firm, Lane Powell filed a lien on our judgment for another $384.881.66. On October 5, 2001, Lane Powell rebuffed our attempts to negotiate and filed a lawsuit against us in the Superior Court -- before the judgment on the Windermere lawsuit had been filed and the satisfaction of judgment paid. In December 2011, Lane Powell demanded another $57,036.30 in "interest." That's right! Lane Powell is demanding approximately $755,170.96 for representing us in a Consumer Protection Act lawsuit which we developed ourselves, long before we hired Lane Powell to take us to trial.

In short, Lane Powell wants a huge piece of our award. And Judge Richard Eadie, who we recently learned is married to Windermere broker Claire Eadie, was assigned Lane Powell's case against us. Pleadings in the lawsuit, Case No. 11-2-34596-3 SEA, can be found here.

See especially our August 9, 2012 motion asking Judge Eadie to recuse himself and our August 16 followup reply.

Legalizing Crime in Washington: The Windermere Prototype

Washington Attorney General Rob "Rex Lex" McKenna heads the "Consumer Protection" swindle in Washington. Government regulatory agencies shield old boy networks and predator corporations by allowing them to violate state laws. When citizens object, McKenna goes to court to defend the complicit agencies, saying he is statutorily obliged to do so.

But McKenna

takes the opposite tack if the mood strikes him. For

example, his office argued before the Court of Appeals

that it had no obligation to defend Judge Richard B.

Sanders. See State

of Washington's Court of Appeals brief, 2006.

McKenna also tells the Supreme Court his office has no

duty to represent the Washington Department of

Natural Resources (cached).

The

reader

may

be

interested

in

AG's

arguments

to the Supreme Court (cached).

In 2004,

Redmond CPA Ed Clark reported another accountant's

unethical conduct the State Accountancy Board. In

response, the Accountancy Board tried to silence Mr. Clark

with false charges and extortion. And when Rob

McKenna was informed of the Board's attempt to shake down

a whistleblower, how did he respond? McKenna’s

office backed the Board. To defend his good name and

his CPA license, Mr. Clark spent $800,000 of his own money

fighting the State's legal machine. See: Redmond

accountant to get $500,000 settlement, Seattle

Times, October 20, 2009, and Where’s the

accountability on accountancy board? The Olympian,

November 12, 2009.

The Washington Attorney General holds to the pre-Magna Carta legal theory that Rex Lex ("The King is the Law"). That is, whenever a government executive speaks from the throne, those utterances carry the force of law.

In most other states, the pillage and plunder combine that McKenna protects might be called "organized crime." In Washington, it's called "consumer protection."

On November 10, 2010, at a Washington Coalition for Open Government meeting, we asked McKenna what he intended to do about the refusal of the Department of Licensing to apply state law to the region's largest real estate company. McKenna admitted he was familiar with the facts, smiled, and replied that he would do "Absolutely nothing." See Carol DeCoursey's affidavit. Now see what McKenna permits.

Windermere

A Realtor® can separate

some poor sucker from his life's savings in a single

transaction. No other game offers that same

challenge, thrill, reward, and satisfaction. And

to have the cooperation of the Department of

Licensing?— Sweet! (See DOL complicity here.

See Attorney General's complicity here.)

- Web page of another

Windermere Victim

John W. Jacobi, founder of the Windermere syndicate. (Photo credit, cached) Jacobi is a powerful political force in Washington (source, cached). If Jacobi wanted Windermere to live up to "the highest of ethical standards," it would.

Jill Jacobi-Wood, President of Windermere Real Estate Company, daughter of John, and wife of Geoff Wood. (Photo credit, cached.) Jacobi-Wood plays a vital consulting role for the senior management team on day-to-day business operations. (Source, cached.) If Jacobi-Wood wanted Windermere to live up to "the highest of ethical standards," it would.

Geoff Wood, CEO of Windermere Real Estate Services Company ("WSC"). (Photo credit, cached.) Wood is married to Jill Jacobi-Wood and is Jacobi's son-in-law. If Wood wanted Windermere live up to "the highest of ethical standards," it would.

WSC is the brand owner and franchiser of the Windermere name, controller of Windermere's policies and procedures, public relations, and legal strategies.

Chris Gregoire, Governor of Washington State. In March 2005, Gregoire appointed Liz Luce Director of the Department of Licensing. Gregoire also appointed three (3) Windermere licensees to the Real Estate Commission (Cate Moyé, Dan Murphy, and Jeff Thompson). On, April 22, 2009, Gregoire was informed by letter of the facts on this page — or at least the people with whom she has surrounded herself were informed. But Gregoire did not answer — she simply passed the letter on to the DOL. If Elliot Ness received a report that Al Capone was dodging his federal taxes, would Ness pass the complaint on to Capone to answer? Maybe such letters need to be wrapped around political favors.

On May 21, 2009, Ralph Osgood, DOL Assistant Director, responded on Gregoire's behalf. Osgood dodged the evidence of Windermere's pattern of abuse and DOL's complicity, and pretended the letter was about Paul Stickney.

On May 29, 2009, DeCourseys wrote to Gregoire again. And again, no response from Gregoire. On June 19, 2009, Carol DeCoursey spoke by telephone to "Cheryl," one of Gregoire's assistants. Cheryl refused to give her last name or her email address, admitted having the April 22, 2009 letter and Osgood's response, but told Carol emphatically that Gregoire "stands behind the DOL."

At this point, there can be no further question: The bucket of blood on this page is how Gregoire wants to run the state.

Liz Luce, Director of the Department of Licensing until June 30, 2011, appointed by Gov. Gregoire. (Photo credit, cached) Luce stated she was "a strong believer in delivering the best possible service to the citizens of Washington." Unfortunately, she was not specific about which "citizens of Washington" she was so eager to service. Luce even said she "would appreciate feedback on the services we provide" (source). But Luce was too busy providing her services, it seems, to answer the "feedback" concerning some of the facts on this page. See correspondence.

Rob McKenna, Washington's Attorney General, elected for the terms beginning January 2005 and 2009. McKenna is surprisingly supine while Windermere profits from the sale of a meth lab house to unsuspecting buyers.

We’ve had prior bad experiences with Rob McKenna, but nonetheless, we wrote to him on June 15, 2009 asking him to stop the DOL colluding with Windermere to flout Washington real estate law. We gave him specific examples and court decisions with documentation.

On July 2, his office responded: McKenna supports DOL’s decisions on Windermere, McKenna will do nothing to enforce state law, and McKenna would defend DOL if anyone challenged its decisions. On July 13, we asked why McKenna thinks it’s OK to allow Windermere to sell a contaminated meth lab house to unsuspecting buyers without even a hint of disapproval? How does his permissiveness help Washington consumers and his war on meth?

Readers of this page will see his answer

here — as soon as it arrives. So far, it seems

Washington is like some Central American nightmare, where

the rich get richer and the poor get drugs — even if they

don't want them.

Under the US Constitution, a state AG

has no business in foreign affairs. Yet in 2009

McKenna — as Atty. Gen. of Washington — signed a statement

of support for Israel's actions in Gaza. Isn't he a

little confused about his job responsibilities? See

The Seattle Times,

September 1, 2009.

Rodney Tom, Washington State Senator for the 48th district. (Photo credit) Tom is also an associate broker at Windermere Real Estate/East, Inc. ("Windermere Kirkland-Yarrow Bay"). Those facts are not completely disassociated: In his real estate promotional material, Tom advertises he is a state senator (cached, cached).

Tom is serving his first term in the Senate, but as a rookie, he was installed on some very important committees: Early Learning & K-12 Education, Judiciary, Ways and Means, and Consumer Protection and Housing. (Source)

A Windermere associate broker on the Consumer Protection and Housing Committee??! How very convenient. And Windermere boasts of its political power.(source, cached)

Sometime after RenovationTrap.com drew public attention to the conflict of interest inherent in Tom's position on the Consumer Protection and Housing Committee, the committee was disbanded. See here for details.

DeCourseys reside in the 48th district, making Tom their state senator. On April 15, 2009, DeCourseys wrote to Tom asking his help putting law and order back into Washington Realtor® business by having a court issue a Writ of Mandamus (definition) on the Department of Licensing (see letter here). Sen. Tom has not answered that letter. DeCourseys have called his office numerous times and asking for a constituent visit — still no answer. As soon as things change, you will see it here.

Sen. Tom has national political ambitions; he wants to run for Congress. If he attempts to have state law enforced on the Windermere syndicate, would he still have access to the Jacobi/Windermere fortune, connections, and political machine?

Like, is Tom's silence due to a conflict of interest?

June 11, 2009: DeCourseys nudged Tom.

June 24, 2009: Senator Tom called DeCourseys at home, accused them of lying, and said he is not a Windermere broker.

Charles McMillan, president of the National Association of REALTORS® (NAR). (Photo credit) NAR, whose members are known as "Realtors"®, is North America's largest trade association. As of November 2008, NAR represented more than 1.2 million members. Windermere agents are all members of NAR. (source, cached)

According to the Realtor website, compliance with the Realtor Code of Ethics is enforceable and enforced on each Realtor:

"In recognition and appreciation of their obligations to clients, customers, the public, and each other, REALTORS® continuously strive to become and remain informed on issues affecting real estate and, as knowledgeable professionals, they willingly share the fruit of their experience and study with others. They identify and take steps, through enforcement of this Code of Ethics and by assisting appropriate regulatory bodies, to eliminate practices which may damage the public or which might discredit or bring dishonor to the real estate profession." (source)

All Windermere agents and brokers are required by contract to be Realtors and abide by the Realtor Code of Ethics. (source, cached) But as far as we have been able to determine, none of the people on this page has been disciplined under the NAR Code of Ethics. The NAR Code of Ethics seems to be a meaningless sales gimmick and nothing more.

National Association of REALTORS® (NAR) wields substantial power as a lobbying organization on behalf of agents and brokers; in 2005, NAR had the largest Political Action Committee in the United States. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the association is the United States' third-largest donor to political campaigns, having given since 1990 more than US$30 million. Of this sum, an average of 47% has gone to Democrats and 53% to Republicans. Key political issues for the group revolve around federal regulation of the financial services industry. (source)

Rich Gangnes is the owner and designated broker of Windermere Real Estate/Wall Street, Inc. (Photo credit, cached) Gangnes was the designated broker in the Jonet and Doorish cases. Gangnes has not been disciplined by the National Association of REALTORS® or the Washington Department of Licensing, and still represents Windermere.

Jake Jacobsen is the managing broker of Windermere Real Estate/Wall Street, Inc.. (Photo credit, cached) Jacobsen was a licensed broker in the Rodriquez, Jonet and Doorish cases. Jacobsen has not been disciplined by the National Association of REALTORS® or the Washington Department of Licensing, and still represents Windermere.

Kelly Muldrow, sales manager for Windermere Real Estate/Kingston Inc., fired [name withheld by victim's request] within hours after learning she danced the burlesque on her own time. Muldrow told reporters that McDonald's personal life was "incompatible with the culture of Windermere Kingston." (The Stranger, March 8, 2007.)

In court, Windermere frequently argues that the agents are not agents of Windermere — they are just independent contractors and Windermere has no control over their actions. The Muldrow incident demonstrates otherwise. Windermere fired this agent for her artistic expression on her own time, but routinely retains agents who rip off their customers.

So far, we know that Windermere flagrantly violates:

- the Washington Law of Real Estate,

- the Realtor's Code of Ethics,

- Windermere's Standards of Practice (cached),

- Windermere's Mission Statement (cached),

- the Gospel's Golden Rule,

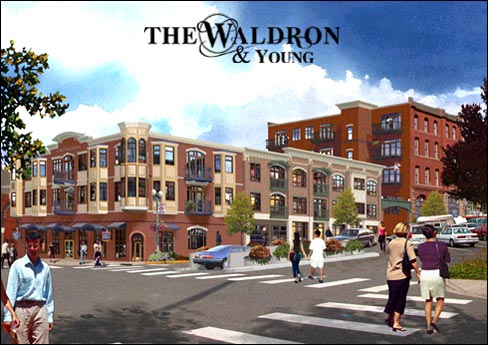

The Waldron & Young Condominium Complex, recently completed in the historic Fairview area of Bellingham, WA. The sales are brokered by Windermere agent Joanne Wyatt of Windermere Real Estate /Whatcom, Inc. (dba Windermere Bellingham-Bakerview). According to Wyatt's web page in about August 2009, four units were still for sale at the combined asking price of just over $5 million.

But an April 3, 2009 inspection report, written by reputable home inspector George Guttmann, identifies serious construction defects in the Complex.

On August 26, copies of that report were sent to agent Wyatt and the owner/broker of her agency, Dan Washburn. Copies were also sent to Geoff Wood and Jill Jacobi-Wood, co-CEOs of Windermere Real Estate Services, Company. The cover letter reminded those Windermere parties of their legal obligation to disclose "all material facts [that substantially adversely affects the value of the property] known by the licensee and not apparent or readily ascertainable to a party." (RCW 18.86.030(1)(d) and RCW 18.86.010(9))

Will Wyatt, Washburn, Wood, Jacobi-Wood, and Windermere follow the pattern of deceit documented in these pages, and decide to withhold this vital information from potential buyers? Or will Windermere "deal honestly and in good faith" as the law requires?

Lee McDonald, Bellingham resident and owner of a Waldron-Young condo, tells what happened when he asked the Attorney General of Washington, Rob McKenna, to enforce the Subdivision Act of Washington to protect Washington consumers.

![]()

The Seattle Times exposes small-time scamsters, but won't publish the misdeeds of the Windermere Real Estate empire. Nor will it expose the role of the Department of Licensing and the Attorney General in allowing Windermere's predation to continue. Here is our May 2, 2011 letter to Jim Neff, The Times investigative team leader.

Maria Kalafatich of Windermere Commencement Associates (photo credit, cached). On May 9, 2009, Andrea Figueira and Silver Legacy Ventures, Inc., filed a lawsuit against Windermere, its agent Kalafatich, and Leslie Walters in Piece County (Case No. 09 2 08671 6). Plaintiffs charged Kalafatich with, among other things, fraudulent concealment and violation of the Consumer Protection Act. Uncharacteristically, Windermere settled with plaintiffs before trial.

On May 15, 2011, we write to Windermere to ask for details — could it be Windermere is changing its policy toward aggrieved clients? We will post Windermere's response here when we receive it.

Windermere is the largest real estate firm in the Northwest (cached) and a company of immense wealth. It was founded by banker John Jacobi and is owned by the Jacobi family. Windermere pretends it is a good corporate citizen: Windermere boasts of sponsoring the arts, a program to benefit the homeless, sporting events (the Windermere Cup), and other community services. Of its business practices, Windermere boasts:

"The

highest

ethical

standards.

Uncompromising honesty and integrity."

But Windermere's business ethic, like its claim to charity, is a public relations gimmick: It is a mask to hide its true nature.

Windermere's Predatory Business Plan

Windermere knowingly allows unscrupulous agents to prey on trusting customers. When a customer complains, Windermere immediately turns the matter over to its lawyers (Demco Law Firm) who boast of being "strong anti-settlement."

"Many of our business clients have adopted a strong anti-settlement posture in an effort to discourage nuisance claims. We support this approach ..." — http://demcolaw.com/about.html (cached)

No matter what wrong the agent has committed, Demco lawyers refuse to handle the complaint amicably. They force the customers to either eat their losses or sue. And when a customer sues, the Demco lawyers use "scorched earth" tactics to multiply the customer's legal bills until the customer runs out of money.

"The firm maintains a vigorous motions practice ..." — http://demcolaw.com/about.html (cached) In Case 06-2-24906-2-SEA, legal expenses have topped $500,000 and are still rising. Plaintiffs won in trial court, but Windermere is using AIG's Seattle law firm to appeal, and that process has only begun. See http://RenovationTrap.com

Then Windermere offers to settle for a fraction of the actual damages and demands an onerous secrecy agreement that the Demco lawyers call the "Dark Clause." The Dark Clause strips the customers of free speech rights and keeps Windermere's business practices secret.

Should a customer persevere and win in trial court, Windermere goes to the Appeals Court and often to the Supreme Court, trying to have the case thrown out on a legal technicality. And a portion of every Windermere commission goes to support Windermere's legal war machine and the courtroom aggression of Windermere's law firm, Demco Law.

Is this "The highest ethical standards … Uncompromising ethics and integrity"?

Windermere agents know that anything goes as long as they keep Windermere rolling in money. Sponsoring "good corporate citizen" programs costs comparatively little and provides a wonderful cover.

None Dare Call It Organized Crime

"Organized Crime refers to those self-perpetuating, structured, and disciplined associations of individuals, or groups, combined together for the purpose of obtaining monetary or commercial gains or profits, wholly or in part by illegal means, while protecting their activities through a pattern of graft and corruption." — Internal Revenue Service Manual 9.5.6.1.1 (07-29-1998)

For all the harm they do society, these business practices require criminal prosecution. Surely the Jacobi beneficiaries, the Demco lawyers, and the marauding real estate agents should face prison terms. Windermere has no fear of the government, however. Through some magic of politics known to the rich and powerful, Windermere predators have little to fear from the Washington Department of Licensing, the Real Estate Commission, or the Attorney General. The DOL regularly picks off single-shingles and small agencies for minor offenses like missing records, failing to supervise agents, or failing to respond in time to DOL document requests. See DOL's list of disciplinary actions (page cached June 18, 2009).

But for Windermere agents and their brokers and employers, there never is heard a discouraging word, and the skies are not cloudy all day. The one exception seems to be Sonya Eppig, whose license was suspended for three (3) months — a full seven years after her offense. But notice it was only foot-soldier Eppig who took the hit, not the agency and agency brokers, despite the court finding that they were equally to blame.

Compare Eppig's offense and her penalty with the offenses and multi-year suspensions dealt to other licensees from other companies.

When a small-shop agency is closed down by the DOL, where does its business go? Who services the stranded customers? Never fear, here's Wind-er-mere, the region's big, politically powerful, take-no-prisoners real estate firm to fill the vacuum.

Funny how it works that way. Now a review of some cases:

The Meth Lab House

Eddie and Eva Bloor moved to Longview, Washington from Missouri and bought a home from Robert and Charmaine Fritz in August 2004. Lance Miller of Windermere Real Estate/Allen & Associates, served as the agent for both the Bloors and the Fritzes in the transaction.

Miller and the Fritzes decided not to disclose to the Bloors that the former rental house had been used to manufacture methamphetamine and grow marijuana. Miller and Windermere knew of the home's history because the same Windermere personnel were active in managing the property as a rental when the drugsters were raided a few months earlier, and they issued the eviction notice on the tenants when they learned of the illegal activity. Everyone in the area was aware of this local news event, including the Fritzes, who discussed it with their neighbors. But then they came to the mandatory question on the Seller Disclosure Statement (Washington law RCW 64.06.020): "Has the property been used as an illegal drug manufacturing site?" Fritz checked "No" while Miller looked on. Later, this form was given to the Bloors.

Soon after the Boors moved in, they learned about the history of the house from the neighbors and local news reports. When Eva Bloor asked the health department about decontamination, the department determined the house was unfit for human habitation and forced the Bloors to leave with only the clothes on their backs. Eddie Bloor had to abandon the tools by which he earned his living.

Bloors sued the sellers, the agent, Windermere, Windermere Real Estate Services Company, and Cowlitz County. A trial court ruled in favor of the Bloors, awarding them damages jointly and severally against the defendants for the claims of emotional distress, loss of personal property and income, loss of use of the property and damage to the couple’s credit. The court also rescinded the sale of the home.

As usual, Windermere appealed. But even with the legalistic arguments of the Demco Law Firm, Windermere lost on appeal, too. (This synopsis cribbed from Nick Gromicko.)

- Washington Department of Health, Meth Lab Fact Sheet: "No one should rent, purchase, or otherwise occupy a house or dwelling which has been used as an illegal drug lab until the property has been decontaminated. ... No decontamination procedure can guarantee absolute safety for reoccupancy."

- July 14, 2009, The New York Times, "Illnesses Afflict Homes With a Criminal Past " (cached)

- January 26, 2007, The Daily News, "Cowlitz County ordered to pay in meth case"

- Fritz and Windermere/Miller both appealed. In an

appeal, the appellant files a brief, the respondent

files an answering brief, and the appellant files a

reply brief. In this case, the Fritz and

Windermere appeals were answered by a single Bloor

brief, making a total of five

briefs for the court to consider.

- Windermere appellant brief

- Fritz appellant brief

- Bloor respondent brief

- Windermere reply brief

- Fritz reply brief

- Washington Court of Appeals Div. II, April 1, 2008, Case No. 35740-2-II, Published Decision (cached)

- April 1, 2009, Board of Realty Regulation Newsletter published by Montana Department of Labor and Industry, Business Standards Division, "Court Decisions" (cached)

- July 13, 2009, New York Times: "Illnesses Afflict Homes With a Criminal Past" (cached)

- See also Meth Lab Homes.

The Rat House

In May 2002, George Rudiger of Windermere Real Estate Northeast, Inc. was the listing agent for a home in Shoreline that was infested with rats. It was only after purchaser Gary Kruger took possession of the property that he discovered the toxic problems: dead rodent carcasses in the walls, chewed out wiring, and extensive contamination of interior structural components with rat urine, feces, and festering rat nests. Kruger also discovered rodent bait stations, concealed rat holes, and wire mesh strategically installed to deter rodents, indicating the problem was well known to the previous owner.

And who was the previous owner? Rudiger's friend of 30 years! The friend bought the home in 1997 for his family, and Rudiger was the buyer's agent. Rudiger's friend then lived there for five years with his wife and young children (and the rats). In a handwritten addendum to that sale, Rudiger recommended rat abatement actions, thereby establishing beyond reasonable doubt that Rudiger had known of the rat problem in 1997. Knowing of the problem, Rudiger was legally required to disclose it to Kruger in 2002 — but did not.

When Kruger discovered the rat contamination and his attorney wrote to Windermere, broker Joan Whittaker "categorically" denied all knowledge on behalf of Rudiger and Windermere. Whittaker wrote:

"Mr. Rudiger categorically denies he had any knowledge whatsoever of the alleged conditions. Indeed if he had such knowledge, he would have seen to it that these conditions would have been disclosed ..." See http://windermerewatch.com.

An ASHI certified inspector wrote of the property:

"In summation, the house is not fit for habitation. All affected insulation, wood members and fibrous finish materials will need to be removed from the structure to correct these conditions. Additionally, rodent chewing has damaged the wiring. This condition causes a fire safety hazard."

Windermere's lies were revealed in the court discovery process.

But despite the documentation, Windermere was able to outspend Kruger in court. When Windermere moved for dismissal of the case in Summary Judgment, Kruger's lawyer demanded an additional $25,000 to represent him at the hearing. When Kruger could not pay, the lawyer withdrew from the case. Kruger went into the hearing without legal representation and Windermere had the case dismissed on a legal technicality.

Kruger filed a complaint against Winderemre with the Department of Licensing. In November 2005, DOL wrote to Kruger that Windermere had done no wrong. But Kruger persisted with followup correspondence, pointing out the anomalies.

When Kruger published his Windermere story on the Windermere Watch website, Windermere sued Kruger for trade libel and defamation. Shortly after serving him the lawsuit, and fully aware Kruger had no legal representation and couldn't afford any, Windermere lawyer Matt Davis emailed him, "In the meantime, you need not hire an attorney," and "Unless and until I tell you otherwise, we will try to resolve this directly and outside the legal system." That is, Windermere tried to fool Kruger into not filing an answer to Windermere's lawsuit, a trick that might win the case for Windermere by default judgment. But Kruger answered without a lawyer.

Windermere's suit against Kruger went to mediation. As revealed in Windermere's mediation brief, Windermere's ultimate purpose was to silence Kruger with the infamous Dark Clause. During that process, Windermere's Atty. Davis revealed that Windermere works hand in glove with the Department of Licensing, Real Estate Division. Davis wrote to the Court that Kruger was "... hounding the DOL without success." How could Davis have known of Kruger's continued efforts to have the DOL enforce Washington State law on Windermere? Davis' letter indicates gossip was liberally traded between the DOL Real Estate Division and Windermere's lawyers at the Demco Law Firm.

In the presence of the mediator, Windermere agreed to dismiss its own suit (under CR 41) and pay Kruger a small sum of money. After dismissing the suit, Davis emailed Kruger that Windermere would be paying nothing, despite the agreement.

- Mirsepasy's Notice of Withdrawal

- Windermere Watch web page

- Washington Superior Court, Case Nos. 02-2-28184-2-SEA and 05-2-34433-4-SEA.

- History of correspondence between Kruger and Washington Department of Licensing

The Toxic Mold House

Judy Bigelow of Windermere Silverdale was Theresa McCormick’s agent when McCormick made an offer on a home in Lakewood, WA in 2003. Bigelow, an experienced agent with more than 20 years in the field, recommended Scott DeSchryver of Lighthouse Home Inspection (cached) to do the building inspection, telling McCormick that DeSchryver was absolutely the best housing inspector she knew. But Bigelow did not tell McCormick that DeSchryver was a friend of her son and relatively new in the field.

Among other things, DeSchyrver missed approximately 1,000 square feet of soft rot fungus in the attic. Orion Labs analyzed the fungus and found it included the species Chaetomium, one of the three most toxic molds listed on Mold-Help.org.

Why didn't Bigelow recommend a solid, experienced inspector? In all her years of practice, she must have found someone worthy of trust. But it seems Bigelow was more interested in doing a favor for a friend than her statutory duty of loyalty to her client. After McCormick discovered the problems with the house, she discovered DeSchryver had no insurance. She then discovered no lawyer wanted to take a case against DeSchryver because no insurance company would be paying the damages, even if she won the case. In an email exchange between McCormick and Bigelow, Bigelow states "there is nothing Windermere can do" since Windermere did not sign the contract with DeSchryver.

McCormick trusted Bigelow’s recommendation. Had she known about the flaws in the home, she would not have bought it. Had she known that DeSchryver was a friend of Bigelow’s son and new to the field, she would have hired a different inspector. McCormick lost hundreds of thousands of dollars as a result, and her family has suffered severe health problems.

Later, in 2007, the Department of Agriculture fined DeSchryver for not reporting wood destroying insects on another home (source). But as of May, 2008, Windermere was still promoting Scott DeSchryver and presenting him to the public as an "expert" at the office of Windermere Silverdale.

"'An Evening with the Experts,' is planned to provide the public with information about various real estate subjects. Guest speakers will be building inspector Scott DeSchryver of Lighthouse Home Inspection ... Where: Windermere Real Estate office, 9939 Mickelberry Road in Silverdale." — Kitsap Sun, Business Briefs 5.12.08 (cached)

Why would Windermere recommend an inspector who has a history of missing critical problems? DeSchryver claims, "We work closely with Puget Sound area Realtors ..." (source, cached) Question: How close would a real estate agent feel toward an inspector who spoiled a sale with bad news? And how careful would an inspector be if he knew that his next job was dependent upon not spoiling the current sale?

- RCW 18.86.030: "Regardless of whether the licensee is an agent, a licensee owes to all parties to whom the licensee renders real estate brokerage services the following duties, which may not be waived: (a) To exercise reasonable skill and care; (b) To deal honestly and in good faith."

- RCW 18.86.050: "Unless additional duties are agreed to in writing signed by a buyer's agent, the duties of a buyer's agent are limited to those set forth in RCW 18.86.030 and the following, which may not be waived except as expressly set forth in (e) of this subsection: (a) To be loyal to the buyer by taking no action that is adverse or detrimental to the buyer's interest in a transaction; (b) To timely disclose to the buyer any conflicts of interest; (c) To advise the buyer to seek expert advice on matters relating to the transaction that are beyond the agent's expertise."

See more about McCormick's story:

- Jan/Feb 2007, Washington Free Press, "Is it safe to buy a home in WA?"

Abuse of a Vulnerable Adult

John Demco, Windermere lawyer and licensed broker, owns/owned the agency Windermere Real Estate /Washington, Inc. in Freeland on Whidbey Island (and various other locations). Two of his agents, Samantha Saul and her mother, Linda Gabelein, had the complete trust of Emma Endicott, a mentally confused, elderly widow who owned 24 acres of Mutiny Bay waterfront-view property.

According to the court findings, Emma had a bruising fall on June 14, 2005. Her sons called 911 and had her taken to the hospital. After Samantha visited Emma the next day, Emma became convinced that her sons had abused her. Samantha and her mother convinced a judge that Emma needed protection from her sons and obtained an order prohibiting the sons from visiting their mother.

Samantha and her mother also persuaded Emma to give Samantha power of attorney over her affairs. Then they persuaded Emma to sell parcels of her property to them and their relatives at prices far below market value. When Emma's sons found out and objected, broker Demco told them the sales were final. The sons were forced to sue. Demco, Matthew F. Davis, and L'Nayim Shuman-Austin defended the agents and Windermere at trial — and lost: The court found the agents had violated Washington's Abuse of Vulnerable Adults Act. Windermere appealed and lost on appeal.

Washington Department of Licensing has been fully informed of the case, but has done nothing. Saul and Gabelein (and Demco, of course) still practice real estate, untouched by the DOL. Saul and Gabelein now have their own real estate agency in the building previously occupied by John Demco's Windermere franchise. Demco has moved his practice down the street.

- June 2, 2006 Whatcom County Superior Court, Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (cached)

- February 4, 2008, Washington Court of Appeals, Case No. 58435-9-I/5; 58531-2-I, Published Opinion (cached)

- February 25, 2008 Northwestlaw's Weblog: "Incapacity; Undoing the Transactions of the Elderly"

Foreclosure Scam

Vila Pace-Knapp trusted Windermere, but never again. In 2001, Windermere agent Dick Pelascini of Windermere Real Estate/Bellevue Commons, Inc. offered to save her home from foreclosure so she would not have to declare bankruptcy. Pelascini and his friend came to her home repeatedly to pitch the deal, and eventually she relented.

Villa fell prey to a con game so classic, it is featured in goverment documents. Villa was told she could rent the home from Pelascini for a few years and then buy it back. But two years later, Pelascini sprung the trap: Villa and her handicapped son were evicted.

Villa sued and won the case in court. "She ultimately lost the home to the speculators who set her up," wrote Judge Suzanne M. Barnett. Pelascini appealed, failed to get the desired dismissal, and appealed again. But the Washington Supreme Court declined to review the case.

Pelascini still represents Windermere and was not penalized by the DOL.

- April 1, 2007 McClatchy Newspapers: As foreclosures rise, scam artists flourish

- March 17, 2008 Washington Court of Appeals, Case No. 59321-8-I, Unpublished Opinion (cached)

- April 1, 2008: Seattle Weekly: "Sold Out"

- December 8, 2008 Supreme Court of Washington Petitions for Review ("Deny [Pelascini's] petition for review; grant Respondent’s attorney fee request") (cached)

- May 5, 2007: The News Tribune (Tacoma): "Home bailout scams on rise"

- Fraud Problem comments on the case

Serial Con Artist

Cheryl Jonet, now deceased, worked

for Windermere

Real Estate/Wall Street, Inc.. Jonet was a

defendant and judgment debtor in numerous legal actions in

Washington, including suits for mishandling earnest money,

breaches of promissory notes, and unlawful detainer.

In February 2005, Peter Doorish was selling a home and

Jonet was a buyer's agent. Jonet told Doorish her

buyer was a lawyer, but the buyer was actually a clerical

worker, a single mother with four children. Jonet

persuaded Doorish to loan the buyer $50,000 (assuring him

that Windermere lawyers would write the papers), kept

Doorish's funds for herself, gutted much of the home prior

to the buyer's occupancy, incurred substantial liens on

the home, told Doorish that the buyer could not sustain

the debts and the home was about to be foreclosed, and

persuaded Doorish to take the property back. After

he recovered the property, Doorish discovered the gutted

condition of the home and its financial

encumbrances. Doorish had to spend hundreds of

thousand of dollars to pay off the lien holders to avoid

foreclosure and restore the home to a livable

condition. Doorish also lost the $50,000

misappropriated by Jonet.

The parties mediated a settlement agreement

and the case was dismissed on February 12, 2010.

Doorish reportedly received no compensation for his

damages.

- December 8, 2009 King County Superior Court, Case No. 08-2-42345-0 SEA, Doorish Summons and Complaint

On September 11, 2007, Tom Mc Makin wrote to John Jacobi and Geoff Wood of Windermere Real Estate Services Company, informing them that Jonet victimized him and his wife with straw-buyer schemes. Mc Mackin informed Windermere of 11 (eleven) other Jonet victims. Windermere did not reply to Mc Mackin's letter.

Jonet worked in collaboration with a loan shark from Countrywide Home Loans, defrauding both lenders and borrowers with her schemes. If Jonet were alive today, and if criminal justice were a perfect system, maybe she would be serving time with others who traveled that path, such as Vladislav A. Baydovskiy, Donata Baydovskiy, Camie Byron, Alla Sobol, David Sobol, Sandra Thorpe, and Viktor Kobzar, all of whom were recently convicted in federal court (cached) of similar practices.

Hidden Conflict of Interest

Carol & Mark DeCoursey arrived in Washington towards the end of 2003 when home prices were rising. Afraid of being forced out of the housing market, in April 2004 they put their trust in Redmond Windermere agent Paul Stickney. Stickney put together a home purchase/renovation package for DeCourseys involving advanced construction and brought a construction company into the deal. Stickney assured DeCourseys he had seen the company's work for years and it was "the best," but he did not disclose to DeCourseys that he had close business alliances with the president of the company. He also did not tell DeCourseys that he had seen the company do only minor cosmetic work (carpets and paint), and that he himself was the registered vice president of the company and 20% shareholder (he later claimed he didn't know.) He was also indebted for more than a $150,000 on a land speculation deal with the president of the construction company. They were behind in their payments, and they used the profits from renovations (whenever possible) to keep the loan current.

As a result of Stickney's undisclosed conflict of interest and the contractor's bungling, DeCourseys' house and finances were ruined. Among many other things, the main hall bathtub was electrified at 110 Volts AC — enough to kill. DeCourseys testified that without those selective (mis-)representations, they would not have bought the property (full story). A lawsuit ensued in which DeCourseys were defendants, counter-claimants, cross-claimants, and third party plaintiffs. The trial court found against Windermere and awarded DeCourseys $1.03 million in damages and legal expenses, but Windermere hired AIG's Seattle law firm to appeal the decision. Since the facts were established by jury, the Windermere/AIG law firm argues that Stickney's actions are permitted by law; they also argues that the trust DeCourseys placed in Stickney was DeCourseys' own error. (Stickney's contractor is now out of business.)

Not satisfied that the verdict and the

judgment were in accordance with law (would a real law

ever permit Windermere to lose?), Windermere took to the

case to the Washington Court of Appeals, naming 14

assignments of error and seven issues on appeal with six

sub-issues. In Matt Davis'

unmistakable style, the brief contains scathing criticisms

of the trial judge, Michael J. Fox. On November

8, 2010, the Court of Appeals returned a decision

trouncing Windermere on every major point, remanding only

a quibble on some costs to the lower court for

recalculation. Windermere was ordered to pay

DeCourseys' attorney fees.

Not satisfiled that the Court of Appeals had

done its job in accordance with law, on January 21, 2011,

Windermere petitioned the Washington Supreme Court to

overturn the jury verdict, the trial court judgement, and

the Court of Appeals decision. Windermere named six

issues presented for review. Again in Davis' unmistakable style, he tried to

portray Judge Fox as incompetent and Court of

Appeals as clueless, calling its reasoning "embarrassingly

wide of the mark" (page 21). "The mark," of course,

would be a decision for Windermere, which the Court of

Appeals had surely missed.

On March 21, former Windermere victims Bloor

and Ruebel filed an amicus

brief, telling the court, "Windermere breaches its

duty to its clients and subsequently litigates against

them to the hilt." Bloor and Ruebel asked the

Supreme Court not to pander to Windermere's methods.

On April 26, the Supreme Court refused

Windermere's petition, sealing the judgment in

stone. Emphasizing the point, the Court ordered

Windermere to pay DeCourseys' attorney fees.

- October 30, 2008 King County Superior Court, Case No. 06-2-24906-2 SEA, Jury Verdict

- November 5, 2008 Seattle Weekly, "The Fixer-Upper From Hell"

- January 23, 2009 King County Superior Court, Case No. 06-2-24906-2 SEA (award of attorney fees and costs, filed February 27, 2009) Final Judgment

- February 6, 2009 Seattle Weekly "Redmond Money Pit Victims Win Half-Million in Legal Fees from Windermere"

- November 8, 2010: Washington Court of Appeals, Docket Number 62912-3, trounced Windermere and upheld the trial court

- See http://RenovationTrap.com.

- History of correspondence between DeCourseys and Washington Department of Licensing

- November 8, 2010: Court of Appeals trounces Windermere, docket number: 62912-3

- January 21, 2011: Windermere launches appeal to Washington Supreme Court

- March 21, 2011:

Windermere victims Ruebel

and Bloor requested

permission to file an amicus

curiae brief (file includes the brief)

- March 28, 2001: Windermere objected to the filing

- March 30, 2011: Ruebel/Bloor answered the objection

- March

31, 2011: The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

gave permission to file the amicus brief, brief filed

- April 12, 2011: Windermere answered the amicus brief

- April 27, 2011: The Washington State Supreme Court denied Windermere's petition for review and ordered windermere to pay DeCourseys' legal fees for answering the Petition. Almost five years after DeCourseys first brought their complaint to Windermere, the case is finally over!

Another Windermere Renovation Disaster

In 2001, a Seattle-area local construction attorney and his wife, whom we will call Mr. & Mrs. J, hired Paul Stickney to sell their current residence and find them another. The house Stickney found for them needed renovation (surprise!). Among other things, it had a hump in the kitchen floor. To make the sale work, the house would have to be renovated and the hump fixed, all within the time available and within budget. Otherwise, they would not want to buy the house.

Stickney discussed with the job with his contractor and reported that his contractor could fix it and the other things in the house on time with quality work. So the J's bought the house and hired the contractor.

This was yet another house sale/renovation package put together by Paul Stickney (see DeCoursey). Stickney convinced the construction attorney and his wife that he knew what he was doing, and he inspired their trust.

Time was of the essence: The purchasers of Mr. & Mrs. J's current resident wanted to move in by a certain date. Stickney did not mention he would benefit financially by referring work to the contractor — but he did tell Mr. & Mrs. J the contractor's wife was sick and the contractor needed the work.

But when Stickney's contractor started work, the story about the hump changed. Now the hump could not be fixed. Soon, Mr. & Mrs. J noticed that renovation was behind schedule. Mrs. J. then found out that the contractor's workers were arriving at the work-site late, leaving early, and charging for an eight-hour day. Mrs. J. complained to Stickney about the contractor's failure to meet the schedule.

Eventually Mr. & Mrs. J. had to fire Stickney's contractor and find another who could meet the now very tight scheduling requirements. The second contractor had to fix plumbing and electrical errors made by Stickney's contractor, with additional expense. When Mrs. J. called "The Stickney Team" office to report the problems with Stickney's contractor, Stickney's associate told Mrs. J. that Stickney's contractor commonly had problem meeting schedule deadlines.

(Stickney's contractor is now out of business.)

Yet Another Windermere Renovation Disaster

|

|

Click on thumbnail

for full-size image.

Click on thumbnail

for full-size image. |

Months later, while insisting Felkers pay his bills, the contractor still would not release the invoices for the materials he claimed to have purchased. Finally, the Felkers smelled a rat and fired Stickney's contractor in 2005, almost a year later. By that time, they had paid the contractor more than $30,000 and they were stuck with a half-renovated house they did not like.

Pictures of the property in the summer of 2007 show the extent of damage to the house beyond the $30,000 paid to Stickney's contractor. The siding and interior doors and trim have been removed, and naked rafters can be seen through the windows. Other pictures later in the year show that Felkers had the house stripped to the frame and rebuilt by another contractor. The cost of the project must have been in the hundreds of thousands, an expense they would probably not have planned when they bought the house.

Felkers lived in rental accommodation for the duration.

The Windermere Name Game

In January

1995, Alexandria Parry was represented by

Windermere agent Marcie Maxwell in

the purchase of a residential property. In the

course of the next two years, Parry learned that the

septic tank was malfunctioning and irreparable, and

further, that the owner and agent Maxwell knew of the

problem prior to the sale and had actively concealed

it. Parry sued. The summons and complaint were

served on the Windermere agency at the correct address,

and the legal papers were given to the Demco Law

Firm. Matthew Davis

represented Windermere. At the proper time in the

progress of the case, Davis signed the joinder form,

attesting that "all parties have been served." Davis

conducted discovery in the name of the defendants and

performed other court duties as though he was representing

them. Two weeks before trial, Davis moved for

summary judgment, claiming the defendant had not been

properly served. Evidence was presented to the court

showing that between the sale of the house and the service

of process, the agency involved (Windermere Real Estate

/East, Inc.) had moved out and another (Windermere Real

Estate /Renton, Inc.) had moved in. The court agreed

and Parry's case was dismissed, despite Davis' statement

on the joinder form deceitfully attesting that "all

parties have been served." Parry then discovered

that Davis had timed his surprise in such manner that the

statute of limitations expired for suing the correct

corporation. Parry petitioned the Appeals Court, but

the Appeals judges affirmed the dismissal. Parry

appealed to the Supreme Court, but that court declined to

hear the case. Parry was stuck with the property and

the loss.

- July 1998 King County Superior Court, Case No. 98-2-17607-5 Parry Complaint

- October 16, 2000 Washington Court of Appeals, Case No. 45831-1-I Published Opinion

The House That Jack Built

In April 2002, Thomas and Diane E. Ruebel took an interest in a Camano Island property offered for sale by Mike Hovis. The Ruebels were represented by Sonya Eppig from Windermere /Camano Island Realty. Hovis had begun remodeling the property in 1995 and the interior was still unfinished. Unknown to the Ruebels, the Camano Island County Building Department had cited Hovis for proceeding without approved engineering drawings and framing specifications. Expert testimony showed that the structural integrity of the building had been compromised. Despite these problems, Hovis added wall covering materials that hid the issues. Before the Ruebels saw the property, an earlier buyer had discovered the legal problems with the house and Windermere became involved in the discussions with the County. When the Ruebels undertook to buy the property, Eppig became involved in the permit and inspection issues, and both Eppig and Hovis made direct misrepresentations to the Ruebels about the status of the dwelling. By means of a vaguely worded addendum inserted into the closing documents, Hovis and Eppig attempted to "disclose" the problems to Ruebels without revealing anything. After the sale was completed, Ruebels learned that the damage to the house was so great, the least expensive solution was to raze it to the foundation and rebuild.

Ruebels sued the seller, Eppig, and Windermere. The jury found Eppig and Windermere jointly liable under the CPA and awarded Ruebels damages and legal fees. Windermere appealed, but the Ruebels prevailed. Washington Court of Appeals Judge Ann Schindler wrote in the Court's opinion that "Eppig helped draft a revised addendum that did not so unequivocally set forth the permitting and inspection problems. And when Camano Realty listed the Hovis property for approximately two years, Camano learned about the permitting and inspection problems but did not inform the Ruebels."

- October 1, 2007 Washington Court of Appeals, Division I, 33-9-I Unpublished Opinion (cached)

Though the following cases do not involve home transactions, they are listed here because they illustrate the Windermere culture and character of its management.

Windermere Condoned Rape, Says Court

The following information is summarized from the U.S. Court of Appeals decision. According to that decision:

In 2000, Maureen Little was employed by Windermere Relocation Services, Inc. as a Corporate Services Manager, a position that required her "to develop an ongoing business relationship and relocation contacts with corporations in order to obtain corporate clients needing relocation services for their employees." Until she was fired, she received only positive feedback from her supervisors. Windermere's records confirm that during the relevant period, Little had the best transaction closure record of all corporate managers by a large margin.

One of Windermere's corporate goals was to have the Starbucks Corporation as a client. Some time in 1997, Little performed some relocation services on a contract basis for Starbucks Human Resources Director, Dan Guerrero, and she learned from him that Starbucks was dissatisfied with its primary relocation provider. Windermere President Gayle Glew told Little that he would "do whatever it takes to get this account" and that Little should "do the best job she could." Thus, Little believed that, as part of her job, she was to build a business relationship with Guerrero to try to get the Starbucks account, and she had at least two business lunches with Guerrero toward this end.

On October 14, Little accepted Guerrero's invitation to discuss the account at a restaurant. After eating dinner with Guerrero and having a couple of drinks, Little suddenly became ill and passed out. She awoke to find herself being raped by Guerrero in his car. She fought him off and jumped out of the car, but again she became violently ill. Guerrero put her back in the car and took her to his apartment where he raped her again. Little fell asleep, and when she awoke he was raping her again. Afterward, he showered and drove her to her car.

Chris Delay, Windermere Director of Relocation Services, warned Little not to tell any of the other executives in the office about the rape. Apparently, he did not want Windermere put into a position where it must confront big-ticket customer Starbucks. Eventually, when Little told Windermere President Glew of the rape and her reluctance to work on the Starbucks account, Glew reduced her pay: he had discovered Little was not willing to do "whatever it takes." When Little refused to agree to the pay reduction, Glew fired her "because he did not want any 'clouds in the office'."

Little brought suit against Windermere, alleging unlawful discrimination and retaliation in violation of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, and the Revised Code of Washington § 49.60; wrongful discharge in violation of public policy; and intentional, reckless, and/or negligent infliction of emotional distress. The district court granted summary judgment in favor of Windermere, dismissing on all four claims.

Little appealed the dismissal. The Appeals Court accepted the facts as above and ruled:

"In sum, taking the facts in the light most favorable to Little, because her employer effectively condoned a rape by a business colleague and its effects, Little was subjected to an abusive work environment that 'detract[ed] from [her] job performance, discourage[d] [her] from remaining on the job, [and kept her] from advancing in [her] career[].'" (quoting from 510 US, 114 S.Ct. 367, Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc.

The case was remanded to Federal District Court for trial, and the parties agreed on an out-of-court settlement.

This case demonstrates far more than the callous greed of a single Windermere employee. Windermere as a corporation circled the wagons to defend Glew's actions and prevent Maureen Little from recovering damages after the miserable events cited above. And according to one Internet source, Glew was still president of Windermere Relocation in November 2008 (cached).

- September 14, 2001: Seattle Times, "Appeals court reinstates harassment suit" (cached)

- September 12, 2001: United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Case No. No. 99-35668, Maureen Little, Plaintiff-Appellant v. Windermere Relocation, Inc., a Washington Corporation, Defendant-Appellee

The Windermere Way

Roberto Rodriguez was an agent for Windermere Real Estate/Wall Street, Inc. from 2003 until April 2005, when his employment was terminated. At that time, Windermere owed him $16,800 in commissions from a joint listing with Sara Thompson that had sold in January. His severance papers from Windermere acknowledged the debt. However, when the sale finally closed in December, Windermere informed Rodriguez that they would be paying him only 20% of the commission (as a referral) rather than 50% as a joint listing. When repeated requests for the entire amount were not productive, Rodriguez sued. As Professor Emeritus Runkel writes:

Roberto Rodriguez sued his former employer, asserting state law claims for unpaid commissions. The employer moved to compel arbitration, but the trial court denied the motion. The Washington Court of Appeals affirmed, agreeing with the trial court that the arbitration agreement was inherently unfair and unenforceable. ... As the court put it: Windermere provided the contract, wrote the arbitration procedures, and selects the arbitrators. The arbitrators must be solely from current employees within the Windermere franchisee family. The arbitrators are all brokers or agents of sister franchisees, which have a continuing, mutually beneficial relationship with the franchisor. The arbitrators are expected to reflect the Windermere Way. The "Windermere Way" may mean that it is in the interests of Windermere Wall Street to have the commission in dispute paid to a continuing employee rather than to someone whose employment it has terminated. We conclude the potential arbitrators have a known, existing and substantial relationship with the party-franchisee. On these facts, the process does not satisfy the neutrality requirements of the arbitration statute. We affirm the trial court’s denial of the motion to compel arbitration. — How not to write an arbitration clause, February 04, 2008 by Ross Runkel at LawMemo

Windermere argued that Windermere agents not an employees, they are independent contractors. But the judges laughed as only judges can laugh: They used the words "employees," "employment," and "employer" sixteen (16) times in the decision. For example: "He signed a broker/sales associate agreement which designated him as an independent contractor ... In April 2005, Windermere Wall Street terminated Rodriguez’s employment."

Windermere appealed to the Washington Supreme Court, but the court refused to review the decision. As of May 2009, the parties are back in King County Superior Court to decide the case on its merits, Case No. 06-2-35308-1.

- January 28, 2008 Washington Court of Appeals, Case No. 59526-1-I Published Opinion (cached)

Building a Client Base

In 2001, MacPherson's Property Management, Inc. filed a federal anti-trust suit against Windermere and certain Windermere employees who had previously worked for MacPherson's. According to court testimony, in the last few weeks of their employment with MacPherson's, the Windermere defendants photocopied MacPherson's client list and transferred it to the Windermere premises. The defendants wrote to approximately sixty MacPherson clients, announcing their plans to move to Windermere and urging the clients to transfer their property management accounts to Windermere. Among other things, MacPherson's claimed theft of trade secrets and anti-trust violations.

Court testimony also revealed that those turncoat MacPherson employees were former Windermere employees, apparently sent into MacPherson's for the purpose of this double-cross.

Marsha J. Pechman, United States District Court Judge, ruled that MacPherson client lists were not trade secrets because Windermere could have gotten the client's names and addresses from public records.

But, Judge, if Windermere could get the names and addresses from public records, why didn't they? Why was Windermere allowed to benefit from what most ordinary mortals call "theft?"

MacPherson's appealed but lost on appeal.

- May 25, 2004 United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, [U] Macpherson's, Inc. v. Windermere Real Estate Services Co., Case No. 20040525, Unpublished Opinion

Is Your Real Estate Agent a Convicted Murderer?

|

James J. Bondsteel, with a

conviction for negligent murder and a four-year

prison term in his past, had no problem obtaining a

real estate broker license in Washington (photo: The Coloradoan).

In

Washington, we don't hold little things like a

murder conviction against our license

applicants. After all, a it could happen to

anyone, right? |

In 1992 when he was 21, James Jed Bondsteel

shot his roommate through the heart with a high-powered

rifle. The victim was a good friend from high

school. In a plea bargain, Bondsteel pleaded guilty

to negligent homicide and spent four years in prison (source,

cached).

But in 2003, Bondsteel had no problem

obtaining a Washington real estate license. The DOL

knew his background -- or could and should have known (RCW

18.85.041(4)).

Bondsteel apparently worked for a

non-Windermere firm for a year or so, then was issued a broker's

license (cached)

and later permitted to opened

his own office (cached)

called "TeamBondsteel" where he would have no supervision.

In 2009, Bondsteel's career in real estate

was interrupted when he was arrested in Colorado for

attempted rape, kidnapping, and assault. Further

investigation turned up a number of related incidents, and

in May 2011, Bondsteel was found guilty of 18 felony

counts.

After the 2009 charges, DOL suspended

Bondsteel's license for only ten (10) years! After

Bondsteel finishes his upcoming prison term for the 18

felonies, he may be back selling real estate in

Washington.

- October 1, 2009: The Man on the Trail, published by The Crime Diary (cached)

- February 12, 2003: DOL issued real estate broker license to James J. Bondsteel (cached)

- TeamBondsteel, licensed to sell real estate from (3117 W 21st Ave, Spokane, WA 99224 (cached)

- May

2010: Bondsteel's real estate license suspended

for 10 years (cached)

- April-May 2011: CBS News coverage of the Bondsteel trial in Loveland, CO (cached)

- April

19, 2011:

- April 29, 2011:

- May 5, 2011: Jury finds Bondsteel guilty on 18 of 23 felony counts

- April

28, 2011: Testimony of Bondsteel's wife, Tami

(cached Page

1, Page

2, Page

3)

Is Your Windermere Agent a Convicted Thief?

|

Nick Granly, sales agent with Windermere Real Estate/Valley, Inc. in Spokane Valley, Washington. (Photo credit, cached) According to a 2004 article in the Spokane Review, Granly has a colorful past. |

As illustrated by the cases here, Windermere takes no responsibility for the damage caused by its agents and brokers. In passing from the glossy promotion language to its legal arguments, Windermere's "best people" become "independent contractors" for whom Windermere takes no responsibility.

But let's look at reality: What care and diligence does Windermere exercise in hiring the "best people" (cached)?

In Spokane Valley, Washington, a real estate agent named Nicholas Granly works through Windermere Real Estate/Valley, Inc. and enters homes while the owners are gone, manages contracts and multi-thousand dollar good faith deposits, renders advice to people on investing their life savings, and answers to no one about any of it. (Source, cached)

But according to the Spokesman-Review, Granly has prior felony convictions for robbery, burglary, and theft. At one point, Granly was involved in a shotgun standoff with the Spokane sheriff's office. (Source, cached).

We asked several of our local bankers whether they would hire someone with a prior felony conviction, and they rolled their eyes and laughed. No, bankers would never take that chance with their customers' assets. So why does Windermere expect real estate customers to shoulder the risk?

As soon as you list your home for sale with any company, Granly (and any other agent in Washington with a questionable background) gets unrestricted access to your home, your mail, your financial records, and your most personal belongings, including jewelry and heirlooms. Unless you take an inventory every day when you leave and return, you have no idea whether Grandma's broach is still where you left it. And you would still not know whether some agent paid you a visit and found your bank account numbers, copied your spare keys, or maybe cloned your computer disk.

The Windermere web page gives no evidence that Nick Granly or any other agent is bonded.

Granly's boss is Windermere franchise owner Catherine Moye. Moye was appointed to the Washington Real Estate Commission by Gov. Christine Gregoire. (Source, cached) The Governor's press release reveals that Moye is a member of the Spokane Association of Realtors professional standards committee and is the vice president and president-elect of the Spokane Symphony.

Among the thousands of Windermere agents and brokers, how many have a criminal history? Our bet is that the Governor, the Department of Licensing, and Windermere Real Estate Services Company just don't know — or care. When you have a legal firm like Demco Law to chew up and silence your unhappy customers, why worry?

Arizona Offices Dumping Windermere Brand

Jan. 25, 2010 — Sometime in January 2010, Windermere went dark on the Arizona skyline.

In December, there had been scores of Windermere agents and brokers working from more than 20 offices throughout the state. Almost overnight, the picture changed. Now there are only two offices in all of Arizona! What happened?

For weeks prior to the mass exodus, activitists for the Windermere victims gave information about Windermere's predatory business practices to Windermere brokers, agents, and customers. For example, see sample postcard. The payload in that postcard is the observation that a portion of every Windermere commission goes to support Windermere's legal war machine and the courtroom aggression of Windermere's law firm, Demco Law.

Windermere brokers, agents, and customers got the message. See this email from former Windermere agent Riana King and the answer from a victim of Windermere.

The information exchange continued …

Then, on January 15, a Windermere activist discovered that 19 of the 21 Windermere offices in Arizona had disappeared from Windermere's Arizona web page. Windermere brokers and agents had proved their decency and respect for fair dealing by dumping the Windermere brand. For example, these former Windermere agents and brokers are now listed on a Long Realty web page.

RUSH TO DUMP THE BRAND — Two former Windermere agents, Jerry and Joy Pickles, are now affiliated with Long Realty. The Pickles were apparently in such a rush to dump the Windermere brand and substitute "Long Realty" on the banner of their new webpage that they inadvertently left in the word "Windermere" in the body of the page. (See cached copy from January 15.)

And Windermere Phoenix ("West Valley") changed the individual web page links on their site to the Long Realty domain — but left the Windermere banner over the page!

In 2007, Windermere had 21 offices in Arizona. On January 14, 2010, Windermere had three offices in Arizona and the Google Net crawler took a snapshot of the site. As this is written, Windermere has only two offices in the entire state — both in Prescott (cached).

No one should be surprised at this huge reversal of fortunes, least of all the billionaires and wannabees who run Windermere. Real estate business is based on customer trust. When you make a habit of abusing customers, business vanishes.

And when honest agents and brokers find out what is happening, they vanish, too.

Falling Windermere Leaves Are Turning Prudential

As recently as 2004, Windermere was still in its ascendance and big names in real estate were joining the company (see Windermere press release, 01/16/2004, cached).

But times and seasons change, and Windermere's "unmatched service approach" (illustrated on this page) is not so attractive. Recently, Windermere Prestige Properties in Los Vegas broke away from Windermere and announced it is merging with Prudential Americana Group, an independently owned and operated member of Prudential Real Estates Affiliates, Inc.

Windermere Prestige Properties (a.k.a. "Windermere Summerlin") grew from a mere 20 agents to 100 agents in the last five years. Despite Windermere's recent promotion of high-tech tools for selling real estate (source, cached), owners Heidi and Peter Kasama say they are taking their huge Las Vegas agency to more consumer-friendly company.

"We found that Prudential offered more value to our agents and clients than any other franchise," said Heidi (source, cached). Obviously, Heidi is no fool. In a business that depends on reputation and references, Windermere's predatory practices and marginal legality are destructive to both clients and agents.

Heidi could have said her clients don't like getting screwed, and her agents don't like getting sued.

SAVE

THIS

NOTICE TO SHOW YOUR ATTORNEY IN THE

EVENT OF A LEGAL DISPUTE WITH WINDERMERE

Legal Process Backfires on Windermere Network

Brokers in Important New Precedent on Privity

In King County Superior Court case number 05-2-34433 SEA, to dispose of a defendant's counterclaims in their defamation and trade libel lawsuit of intimidation brought against a buyer who publicized Windermere lies and its refusal to honor its public commitment to the "highest ethical standards, uncompromising honesty and integrity," franchiser Windermere Services Company and franchisee broker Windermere Real Estate/Northeast-and their lawyer, Matthew Davis argued in a motion for partial summary judgment that "It is true that Windermere Services Company was not itself a party to the first lawsuit, but as the owner of the Windermere trade name, it is in privity with Windermere Real Estate/Northeast."

See fast-loading text scan or signed PDF image of the motion and the order.

Black's Law Dictionary defines privity as:

privity (priv-i-tee) 1. The connection or relationship between two parties, each having a legally recognized interest in the same subject matter (such as a transaction, proceeding, or piece of property); mutuality of interest <privity of contract>

The court agreed with Windermere's argument and granted its motion. But when it was clear that Windermere would face a jury, it voluntarily dismissed its own lawsuit under CR 41, after first pressuring the defendant without success to be silent and sign away his protected speech rights.

While this writer is not an attorney or legal expert, and this news coverage is not intended in any way to be legal advice, it has been noted that privity works both ways, and suggested that the court's ruling on Windermere trade name privity could be interpreted or construed to mean that Windermere Services Company shares automatic mutual liability for any harmful act or violation of law committed by any Windermere franchisee broker, because the parties share the same trade name; and/or that ALL Windermere Network franchisee brokers share automatic mutual liability for ANY OTHER Windermere Network franchisee broker's harmful act or violation of law, through sharing the same trade name. If you are damaged by any Windermere broker or agent, the entire Windermere Network may now be mutually liable.

But while the privity argument was an important part of the dismissal of the counterclaim, Windermere also based its case on res judicata (a thing adjudicated; a case that has been decided). Windermere successfully argued that Windermere Real Estate Services Company is the same entity as Windermere Real Estate /Northeast, Inc. and quoted a definitive decision in that regard to emphasize the point, as follows:

Having lost his claims against Windermere once, Kruger cannot reallege them as a counterclaim in a defamation lawsuit. His claims are barred by res judicata and collateral estoppel.Res judicata, or claim preclusion, applies where a prior final judgment is identical to the challenged action in "(1) subject matter, (2) cause of action, (3) persons and parties, and (4) the quality of the persons for or against whom the claim is made." (Lynn v. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries, quoting Loveridge v. Fred Meyer, Inc., 125 Wn.2d 759, 763, 887 P.2d 898 (1995))[See page 2, line 22 of fast-loading text scan of Windermere's motion and order or for signed PDF image.]

By raising the legal theory of res judicata, Windermere asserted that the persons and parties to the current action are identical to the persons and parties of the previous action. Windermere later argued that "Windermere Services Company was not itself a party to the first lawsuit," then reversed itself once again with the statement that "as the owner of the Windermere tradename, it is in privity with Windermere Real Estate /Northeast [the franchise]. Indeed, that privity is exactly why Kruger targeted Windermere Services with his disparagement." (Page 3, line 12.)

Thus, Windermere argued both sides of the issue: Windermere Services is an identical party with the franchise, but it isn't, but it is; and based on that argument, the Court should grant the Motion to Dismiss. The court agreed that the two entities (Windermere Real Estate Services Company and the franchise Windermere Real Estate / Northeast, Inc.) are identical, as is required for sustaining a res judicata argument, and granted the motion.

Though the decisions of the King County Superior Court are not binding on any other court, nor even on any other case before the same court, the arguments of the parties before the court are binding upon the same parties in other actions in any court through the principle of Judicial Estoppel:

Judicial estoppel is an equitable doctrine that may limit or prevent a party from taking inconsistent positions in separate cases. More specifically, it prevents a party from gaining an advantage by asserting claims, defenses or positions that are inconsistent with those asserted in a prior proceeding and upon which a court relied. — The Double-Edged Sword of Judicial Estoppel by Jennifer Campbell and Christopher Howard of Schwabe, Williamson & Wyatt, P.C.

- November 10, 2010:

In a face-to-face interview, we asked Atty. Gen. McKenna

what he intended to do about the Dept. of Licensing's

refusal to enforce state law. McKenna replied:

"Absolutely nothing."

- November

8, 2010: Court of Appeals trounces Windermere in DeCoursey case

- February 15, 2010:

"Crime Syndicate in Washington?" Flier distributed to WA

Legislature and others.

- March, 19, 2010: "Wide Open Government -- For Big Business." Flier distributed to WA Attorney General's Office and others.

- April

26, 2001: The Washington State Supreme Court

denies Windermere's petition for review. Supreme

Court decision (cached),

full

story.

- March 31, 2011: The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court grants permission to file the amici curiae brief in DeCoursey case.

- March

30, 2011: Bloor

and Ruebel

reply to objection, citing Windermere's "implacable,

take-no prisoners litigation against its clients."

- March

28, 2011: Windermere objects to, among other

things, Bloor and Ruebels' choice of law firms!

- March 21, 2011: Windermere victims Ruebel and Bloor file an amicus curiae brief to the Supreme Court in DeCoursey case citing Windermere's history of breaching its fiduciary duty and wasting its clients with litigation.

John Demco, founder of the Demco Law Firm. (Photo credit) Demco is the legal strongman for the Windermere syndicate, part owner of Windermere Real Estate /Washington, Inc. (UBI 601437503, fact source, cached), and part owner and designated broker of Windermere Real Estate /Washington Referral Resources, Inc. (UBI 601807453). According to records with the Department of Licensing and the Washington Secretary of State, John Demco personally holds business licenses for Windermere agencies in Bremerton, Clinton, Freeland, Langley, Oak Harbor, Poulsbo, and Seattle, and more than one office in some of those communities (info source)

According to his profile (cached), Demco not only practices under the laws, litigates the laws, and interprets the laws to professionals in real estate, he has a hand in writing the laws, too. If he were of good intent, this intense involvement might be a good thing, but close examination shows otherwise.

As part owner of the brokerage and lawyer for the agents, John Demco was a key player in the Endicott case and pushed the case to the Supreme Court, even knowing all the facts. As founder and (until recently) head of the Demco Law Firm, Demco was involved in most of the cases on this page. Demco has not been disciplined by the National Association of REALTORS® or the Washington Department of Licensing, and still represents Windermere.

Matthew F. Davis, lead litigator for Demco Law Firm. (Photo credit, cached) As a litigator, Davis represented Windermere in most of the cases on this page, including Kruger, Endicott, Parry, Campbell, and DeCoursey. Davis has mounted many outrageous legal arguments.

For example, on the second day of the DeCoursey trial, Davis boasted to the judge: "I have had so many cases dismissed because someone did not have a broker to testify as to what the standard of care was, I think that -- but I understand what the Court's position is." (10/22/08 RP 162) That is, though Windermere advertises "the highest ethical standards" to the public, no jury would understand an "ethical standard" without an expert to tell them. And a number of judges, according to Davis' boast, buy off on that theory and dismiss the cases without hearing the evidence.

In a pretrial hearing for the same case, Davis argued that Windermere agents (in this case, Windermere agent Paul Stickney) are not agents of Windermere. According to the Windermere contract, the agents are independent contractors, and Windermere takes no responsibility for anything they do. Davis wrote:

"Stickney Is Not an Agent for Windermere: ... On this record the court should find as a matter of law that Stickney is an independent contractor, and not an agent or employee of Windermere. ... [T]he agreement establishes an independent contractor relationship and expressly disavows any agency relationship." — King County Superior Court, VEMIS v. DeCoursey, 6/16/08, page 2.

Amazingly, Davis cited the Rodriguez case as his authority, a case wherein the judges clearly did not sympathize with that argument.